人質司法とは

日本の刑事司法の実情

日本の刑事訴訟法は、検察官が起訴するまで被疑者の身体を最大で23日間拘束することを認めています。この間、被疑者には取調べを受ける義務があるとの解釈が捜査実務では採用されているため、被疑者が黙秘権を行使しても連日のように取調べが続きます。取調べの最大の目的は、被疑者の自白を獲得することです。

被疑者は、警察の留置場に収容され、警察によって常に監視されます。また、「接見禁止」が付くと、家族や友人など、弁護人以外との面会や手紙のやり取りも禁止されます。起訴前の最長23日間の身体拘束は、別件の軽微な容疑で被疑者の身体を拘束したり、実質的に1つの事件を複数に分割したりすることで、繰り返し行われることが可能です。

起訴後は「保釈」といって、一定の保証金を納めることと引き換えに身体拘束を解くという制度があります(起訴前には保釈は認められていません)。しかし、被告人が無罪を主張したり黙秘をしたりしているときには保釈が認められにくいのです。

このように、罪を認めなければ長期にわたる身体拘束が続くのです。

実際の人質司法の事例

ある男性は、コンビニエンスストアで1万円を盗んだとして逮捕・起訴されました。

その後、男性のアリバイが認められて無罪判決が言い渡されました。真犯人が別にいることも判明し、警察署長から謝罪を受けました。

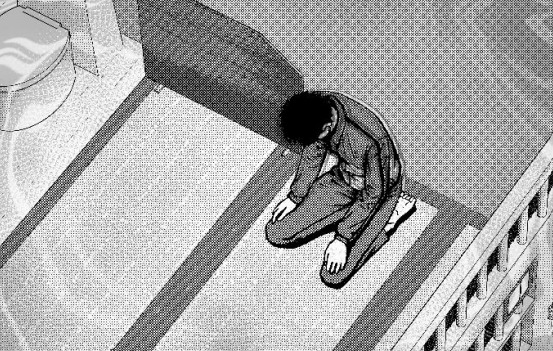

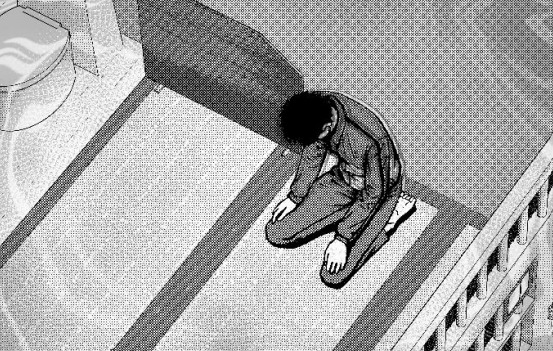

男性は罪を認めずに無実を主張したため、9回もの保釈請求が認められず、10か月間も勾留されました。男性は仕事の関係の契約を解除され、経済的にもキャリア面でも損失を被りました。勾留が長期化し、孤独に苛まれたために、自殺を考えたこともありました。

ある女性は、生後7か月の息子に対する虐待を疑われて傷害罪で逮捕されました。

それは科学的な根拠が疑問視されている「揺さぶられっ子症候群(SBS)」に関する事件であり、医師による「虐待ではない」との意見書を得て女性は不起訴になりました。

しかし、不起訴になるまで不必要な身体拘束を受けました。取調べでは弁護士の助言に従って黙秘をすると伝えたところ、「乳児院の人もお前がいいお母さんの仮面をかぶっているって言っていた。気持ち悪いって言っていた」「お前は異常」など人格攻撃を受けました。また、取調べ中にブラジャーを着用することが許されず、薄着で男性の刑事2人に対応せざるを得なかったことが気持ち悪かったと述べられています。

(Human Rights Watch「日本の「人質司法」保釈の否定、自白の強要、不十分な弁護士アクセス」における土井佑輔氏及びT・ヒデミ氏の事例)

統計からも裏付けられる人質司法

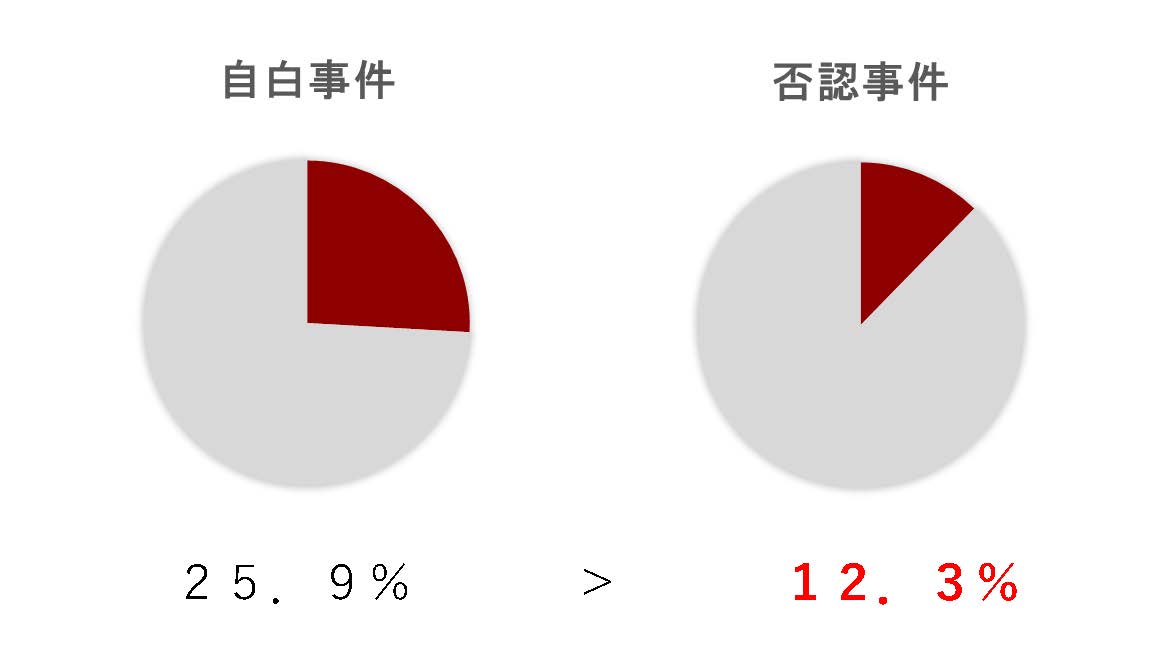

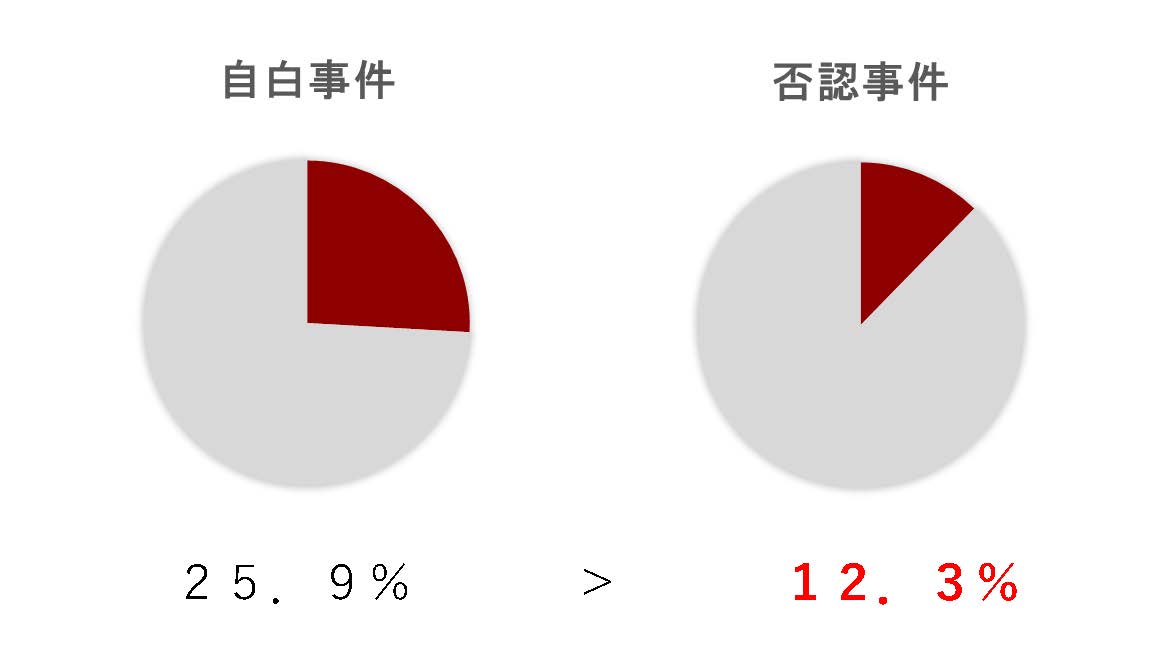

2020年の地方裁判所の第一審における保釈率は、自白している場合が32.1%であるのに対し、否認していると27.6%と、罪を認めなければ保釈がされにくいことが表れています。特に、第1回公判期日前の保釈率は、自白している場合が25.9%であるのに対し、否認事件では12.3%と、顕著な差があります。すなわち、否認していると保釈されないということが統計にも表れています。

第1回公判期日前の保釈率

通常第一審における終局人員のうち保釈された人員の保釈の時期(地裁)(令和2年)より

・人質司法の問題点

人質司法という状況の下では、

①無実を主張する人ほど身体拘束が長くなる

②身体拘束から逃れるために嘘の自白をしたり、検察側の証拠を認めてしまったりする

③その結果、冤罪が生まれる

という問題があります。

罪を犯していないのに逮捕・起訴されてしまう冤罪事件では、一般市民の誰もがこの人質司法に囚われてしまう可能性があります。

人質司法は、国内の学者や弁護士はもちろん、国際的にも強く批判されています。

私たちが求めること

人質司法の問題点を踏まえて、私たちは身体拘束のあり方の是正を求めます。法制度を変えるために国会議員等への働きかけを行い、社会に広くこの問題を伝えるためにシンポジウムなどのイベントを開催します。その際には、「一般市民の声」として本署名を国会議員や刑事司法の関係者に届けたいと思っています。

私たちは、国と裁判所に以下のことを求めています。

- 被疑者・被告人が否認や黙秘をしていることを身体拘束の理由としてはならないこと

- 取調べの時間や方法を国際基準に照らして適正化し、自白を強制したり促したりするような取調べをなくす措置を採用すること

- すべての事件で取調べの全過程を録音録画し、また取調べに弁護人が立会う権利を定めること

- 保釈の運用を、無罪の推定と個人の自由に関する国際基準に沿った運用に改善すること

- 人質司法による冤罪の疑いがある場合には、独立した調査委員会を設置すること

- 被告人の権利や国際人権法上の公正な裁判の規定に関する研修を裁判官、検察官・警察官に対して定期的に実施すること

- 人質司法を解消するための立法を行うこと

(Human Rights Watch「日本の「人質司法」保釈の否定、自白の強要、不十分な弁護士アクセス」参照)

Reality of Japan’s Criminal Justice System

Japan’s Code of Criminal Procedure allows suspects to be detained up to 23 days before indictment. Japanese authorities interpret the criminal procedure code to require detainees to face interrogations throughout their time in detention. Exercise of the right to remain silent does not stop the questioning. The primary goal of interrogation is to obtain a confession from the suspect.

Suspects are detained in the police station detention facility, where there is almost constant surveillance. A “contact prohibition order” also restricts detainees to meeting and communicating only with their lawyers. They are not allowed to meet, call, or even exchange letters with anyone else, including family members and friends. Investigators are supposed to finish interrogating a suspect at the end of the pre-indictment period of 23 days. But they can continue to do so by starting a new pre-indictment detention period by carrying out a new arrest. Police and prosecutors achieve this by detaining a suspect on a separate, minor charge, or splitting a single case into parts.

After indictment, there is a system called “bail,” whereby a person is released from detention in exchange for the payment of a certain guarantee. Suspects are ineligible to apply for bail before indictment and the courts routinely deny bail even after indictment to those who remain silent or those who challenge their charges.

Thus, if they do not confess to their crimes, they are subject to long-term detention.

“Hostage justice” cases

A man was arrested and indicted on suspicion of stealing 10,000 yen (US$90) from a convenience store.

Afterwards, he was ultimately acquitted. It turned out that there was another person claiming responsibility, and the police chief apologized.

Since he did not confess to his crime, his application for bail had been denied nine times and he was detained for 300 days. A contract that he had signed with a record company prior to his arrest to produce an album was cancelled, resulting in financial loss and setting back his career. He said that prolonged detention and the feeling of isolation led him to contemplate suicide.

A woman was arrested on suspicion of abusing her 7-month-old son and charged with causing injury.

It was a case about Shaken Baby Syndrome (SBS), whose scientific basis has been questioned, and the woman was not prosecuted after a doctor’s opinion that it was not abuse.

However, she was subjected to unnecessary detentions until the case was dismissed. As she followed the advice of her attorney and told the police interrogator that she would remain silent, they attacked her character saying that “The people at the infant care institution also said you’re putting on the mask of a good mother. They said you’re disgusting”; “You are abnormal”. In police detention, bras are not allowed. She said that it was very uncomfortable being in a closed room with two male police interrogators while her body lines were visible in her thin clothes.

(Cases of Yusuke Doi and Hidemi T. in Human Rights Watch report “Japan’s ‘Hostage Justice’ System – Denial of Bail, Coerced Confessions, and Lack of Access to Lawyers”)

“Hostage justice” as shown in statistics

In 2020, the bail rate at the first instance in the district court was 32.1% in cases of confession compared to 27.6% in cases of denial, indicating that it is difficult for the bail requests to be approved without confession. In particular, the bail rate before the first trial date is 25.9% in cases of confession, while it is 12.3% in cases of denial, demonstrating a remarkable difference. In other words, statistics show that if the accused deny their charges, they will not be released on bail.

Problems of “hostage Justice”

Under the “hostage justice” system,

- The more the accused claim their innocence, the longer they are detained.

- The accused are pressured to make false confession or admit to prosecutors’ evidence in order to be released from detention.

- As a result, “enzai” – false accusations – occur.

Any member of the public can be trapped in this “hostage Justice” System, as you can get arrested and prosecuted without committing crimes.

The “hostage Justice” system has been strongly criticized not only by domestic scholars and lawyers but also internationally.

What we seek

Based on these problems of “hostage Justice”, we seek to correct the way detentions are used. We will lobby Diet members and others to change the legal system and hold symposiums and other events to inform society at large about this issue. When doing so, we would like to deliver the signatures collected through this project as the “voice of the general public” to Diet members and other stakeholders of criminal justice.

We are asking the Japanese government and the courts to:

- The fact that the suspect/defendant is denying or remaining silent shall not be used as a reason for detention.

- Adopt measures to ensure that the time and methods of interrogation are appropriate in light of international standards and to eliminate interrogations that force or encourage confessions.

- Establish the right to have the entire interrogation process recorded in all cases and the right to have a defense attorney present during the interrogation.

- Improve the operation of bail to be in line with international standards regarding the presumption of innocence and individual liberty.

- Establish an independent commission of inquiry into alleged cases of miscarriage of justice due to the “hostage justice system.”

- Regularly provide training to judges, prosecutors, and police officers on the rights of the accused and the provisions of fair trial under international human rights law.

- Introduce legislations to end “hostage justice”.

(See Human Rights Watch report “Japan’s ‘Hostage Justice’ System – Denial of Bail, Coerced Confessions, and Lack of Access to Lawyers”)